The latest book in the Attack store is Synthesizer Evolution: From Analogue to Digital by Oli Freke. Accompanied by lovely hand drawings by the author the book breaks down a fascinating explosion in the synthesizer market during the last century. In this short hybrid excerpt from the book, we look at a few key moments. The book is out now and available from the Attack store.

The global synthesizer industry was recently estimated by one research firm to have been worth nearly $213m in 2020. This is remarkable considering it only came into being in 1963 with the invention of the analogue synthesizer. Since then, the multitudes of companies around the world have been created to service the demands of this market. This article will offer a brief survey of the evolution of companies in the main countries where synths have been manufactured – America, UK, Europe and Japan, over the course of the late 20th century.

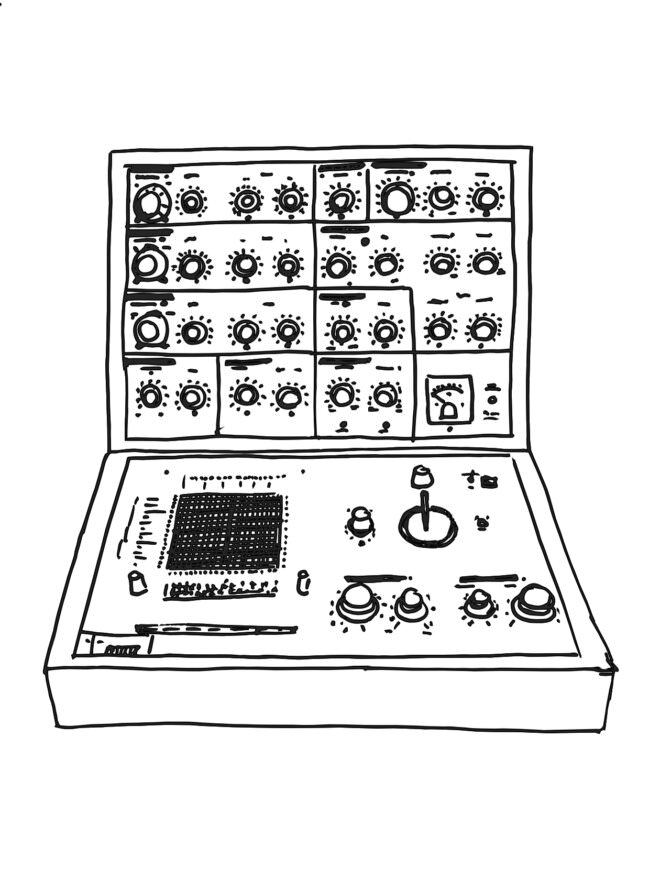

America was the home of the first wave of synthesizer companies, not least because New Yorker Robert Moog was the first to commercialise the modern transistor-based modular synthesizer. His success was quickly emulated by other US firms, such as Buchla EML, E-Mu, and Serge, all focussed on making the new modular analogue synthesizers.

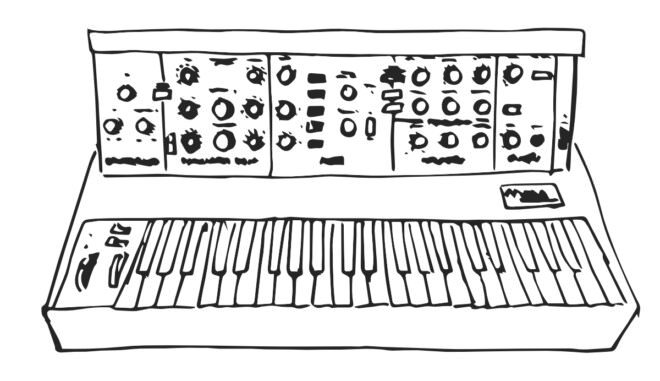

By the 1970s, components had miniaturised such that Robert Moog was able to produce the Minimoog Model D which unleashed another wave of American companies whose name and reputations also still resonate today – ARP, Oberheim, and Sequential Circuits. ARP dominated the 1970s with a huge range of synths including the Quadra, 2600, Odyssey and Omni, which are still revered today.

However, late 20th-century capitalism was a brutal place and most of the above companies had gone bust by the late-1980s. Moog was only ever profitable in 1969, after which the company passed from owner to owner in search of stability and profitability. Robert Moog lost the rights to his own name during this period and only had it restored to him in 2002. Similarly, Tom Oberheim lost the rights to his name when his company was bought by Gibson Guitar Corp in the 1980s, and only had it returned in 2019.

Sequential Circuits went bust in 1987, despite Dave Smith having contributed to the MIDI technical standard in 1982 (along with Ikaturo Kakehashi of Roland), since winning a technical Grammy for the work. Like the others before him, he lost his trademark in the 1980s, but had it returned to him by Yamaha in 2015.

E-mu were one American company that managed to side-step bankruptcy at this time by moving into chip design as digital technologies became increasingly important in early 1980s. This was a good move as Sequential had stopped paying E-mu royalties on their digital keyboard-scanning technology, and which threatened the viability of E-mu during this period.

Dave Rossum of E-mu, however, was involved with the design of the new SSM microchips which he then cannily used to kick-start the American wave of sampling keyboards, with the E-Mu Emulator I in 1981. Ensoniq, another American firm, were also able to ride this wave for a few years before an unfortunate – and typically capitalist – merger with E-mu ended both companies in the early 2000s.

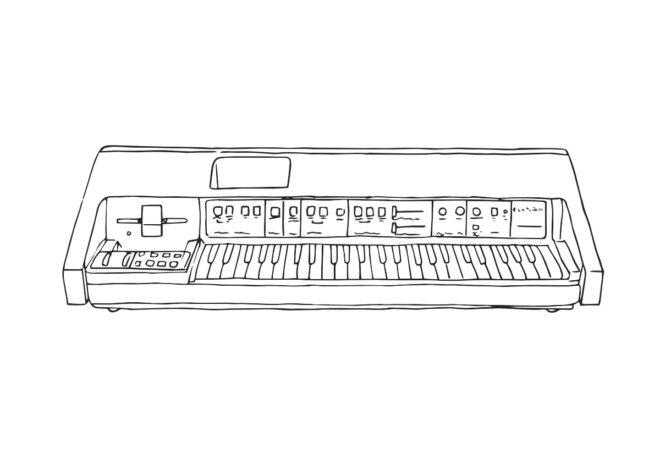

The UK tracked these developments, but on a much smaller scale. EMS were unusual – instead of chasing pure profits, their motivation for selling instruments was to fund their studio activities which were closer to the laboratory-style sound research of the 1950s, dabbling in new computing technology. Very cutting edge – and very expensive.

To this end, they created the VCS3 – a portable synth that actually predates the Minimoog by a year. The VCS3 is famous for its use by Brian Eno on Roxy Music’s Virginia Plain, and another EMS synth, the Synthi AKS was used by Pink Floyd for ‘On the Run’.

However, the strategy of EMS had taken a few wrong turns by the early 1980s and it proved unsustainable. Perhaps they were a little too experimental at a time when the affordable two-oscillator monosynth was king and a £5,000 vocoder (called the EMS 5000) wasn’t quite what the market was after.

The UK produced a whole range of small companies that produced instruments that retain their reputation to this day. The EDP Wasp (1978) was an idiosyncratic black and yellow synth with a membrane keyboard that defied its cheap looks with a killer sound. The Wasp was designed by Chris Hugget, a legend of the UK synth industry, and he was also responsible for another quirky UK synth, the Oxford Synthesizer Company’s OSCar synth (1983). A two-oscillator synth with bizarrely chunky rubber styling and a big sound.

Alongside these well known UK synth companies, there’s a whole swathe of lesser-known ones which I was delighted to uncover during my researches. The Lord Skywave Synthesiser (1977) may have only been represented by one model, but the name and looks are great. Jeremy Lord’s son Simon was a member of the band Simian, which went on to become Simian Mobile Disco. Jeremy himself moved on from synthesizers to medical equipment.

Then there was the KMI Scorpion Stage Synthesizer (1977), which also has a great name, but is now lost to history, as is the JWM Thunderchild (1977) and Watkins Nightshade (1975). Even the UK’s staple of the 80’s high street, Maplin, got into the act, producing several kit synthesizers, which were pretty capable machines. This represented the trend for electrical magazines to produce kits for enthusiasts to build; including Electronics Magazine’s Powertran Transcedent 2000. New Order used a Powertran sequencer on their 1983 song ‘Blue Monday’.

The European synth industry, by contrast, generally developed from existing, older companies and were largely Italian or Dutch. Crumar, Eko, Elka, Jen, Eminent Orgelbouw, Davoli, and Siel were all previously organ or accordian manufacturers who moved sideways into synths.

The organ manufacturers often made polyphonic string or ensemble synthesizers using their ‘divide-down’ electric organ technology. This gave their machines full polyphony, but at the expense of being truly flexible synthesizers. However, they could sound wonderful – as Jean-Michel Jarre’s use of the Eminent 310 Unique on Equinoxe 1 attests to.

Eminent went on to licence their string synth technology to Solina for their String Ensemble (1975); which was also sold in the US as the Arp String Ensemble.

Jen were also an organ maker, and their monosynths – the SX-1000 and SX-2000 – employed their square wave organ oscillators, and used wave-shaping technology to coaxe the other standard synth waveforms – the sawtooth and sinewave – from it.

Japan, of course, has been the home of the most dominant companies since the 1970s – Yamaha, Korg, Kawai, Akai and Casio to name but the largest.

Yamaha and Kawai both began as piano manufacturers in the early 20th century (Koichi Kawai actually having been apprenticed to Torakusu Yamaha in the 1910s). Yamaha started producing analogue synths in 1974 – starting with the massive 8-note polyphonic GX-1.

This led to the CS-80 (1977) – one of the earliest of the consumer polyphonic synths, which immediately gained immortal status through its transcedent sound and musicality. (This Vangelis convincingly demonstrates in his soundtrack to Bladerunner (1982)).

Not content with building the ultimate analogue synth, Yamaha had cannily seen the potential for digital synthesis back in 1973 when they licenced the unproven technology of FM from John Chowning of Stanford University. Working on it for the best part of a decade they eventually launched the breakthrough DX7 in 1983, which then easily became the fastest and best selling synthesizer thus far.

Compared to Yamaha and Kawai, Roland and Korg were late to the musical instrument game, but they soon caught up. Roland emerged from the Ace Tone Company in the 1970s, as Ikaturo Kakehashi left one to form the next. Over the space of just over a decade, Roland created some of the most influential electronic music instruments ever made – the TR-808, TR-909, CR-78 drum machines; the System 500 modular synth; the TB-303, the D-50, Juno 106, Alpha-Juno…etc!

There aren’t many synths and drum-machines that can justifiably lay claim to whole genres of music, but Roland – or Kakehashi – can legitimately lay claim to several – the TB-303 is acid-house and acid-techno; the TR-808 is house and hip-hop, the TR-909 is techno, and even the D-50 was the start of the glossy digital sheen typical of late 1980’s pop.

Korg, too, got their start in the late 1960s, starting with simple electric organs and mechanical drum machines. However, they swiftly moved into synths and created over thirty models in the couple of decades after that. Like Roland and Yamaha before them, they produced one of the top-selling instruments of the day, namely the M1 in 1988. This took the D-50’s digital gloss one step further and gave the world even more realistic emulations of acoustic instruments and the shiny digital synth sounds on which the sound of the late 80s rapidly became dependent.

Curiously, one of the most successful Japanese companies of the 1980s, Akai, did manage to go bankrupt. This is odd as their range of samplers – the S612, S900, S950 and S1000 – were staples of studios and bedrooms everywhere. Quite how they fell out of favour isn’t quite clear. Perhaps their expansion into other studio equipment wasn’t as successful as expected, and at the same time hardware sampling became redundant as computers could now take on that task. The brand name has been passed between various companies since the early 2000s and is now owned by InMusic Brands, who also own Numark and Alesis.

So, as we can see above, the story of the late 20th-century synthesizer companies can reflect the (admittedly stereotypical) characteristics of a nation – America, being innovative and highly capitalist saw the rapid rise and brutal fall of their companies, the UK a nation of plucky underdogs punching above their weight, Japan being ruthlessly efficient in their assessment of a market and having the advanced consumer manufacturing technology to dominate it. And Europe – solid, if unexciting. A bit of a caricature perhaps, but not wholly inaccurate!

Today’s synth market is undergoing something of a renaissance with the rise of interest in modular synthesis in the Eurorack format. This has enabled many small boutique firms to launch new and innovative modules, ushering in another decade of synth industry change and growth!

Original illustrations by Oli Freke

Synthesizer Evolution: From Analogue to Digital by Oli Freke

WHILE YOU’RE HERE…..

Many of the synths mentioned in this article we paid our own particular homage to in the form or enamel badges…!

They are available for £6.99 over on the Attack store!