When the Berlin Wall fell over 30 years ago, young people from East and West came together to celebrate their newfound freedom. Techno provided the soundtrack to this time of unlimited possibilities and was to change the image of the city forever.

The first thing that comes to most people’s minds these days when they think of Berlin is (or at least was until the COVID-19 pandemic) the city’s vibrant nightlife and in particular its techno scene. That was not always the case. Until just over 30 years ago, Germany’s capital was a symbol of the Cold War with a thick wall dividing it right down the middle.

In the east of the city, part of the communist GDR, youth culture was under strict state control. There were no discos, only multi-purpose rooms where tables and chairs were pushed aside in the evening and equipped with loudspeaker boxes, mirror balls and colourful car headlights. Officially, no more than 40% of the songs were allowed to be foreign and by 12 o’clock at the latest the night was over. But like all young people, the teenagers there found ways to rebel against the existing system.

Meeting point for all those who did not want to belong: Alexanderplatz. “We danced and identified ourselves through the music, the dance and the clothes and it didn’t really matter if you looked like a punk or a popper. The only thing that mattered was that you didn’t look like an East German,” recalls Wolfram Neugebauer aka Wolle XDP. Enthused by the robotic movements he had secretly seen in a report about the Frankfurt discotheque Dorian Gray on West German television, Wolle took up breakdancing. The GDR even tolerated him performing on weekends: “Looking back, I feel privileged in my situation growing up in the East.”

West Berlin, on the other hand, cut off from the rest of the FRG by the Wall, enticed with a low cost of living that left room for creative experimentation. Numerous artists settled here: Nick Cave with his band “The Birthday Party”, as well as the “Einstürzende Neubauten”, who used tools as instruments, producing “wild music that fitted into wild Berlin”, as Dimitri Hegemann describes it. Today the owner of the world’s longest-running techno club “Tresor”, the wave of acid house that swept from Chicago via Great Britain to Berlin in 1988 found a home in his former club “UFO”.

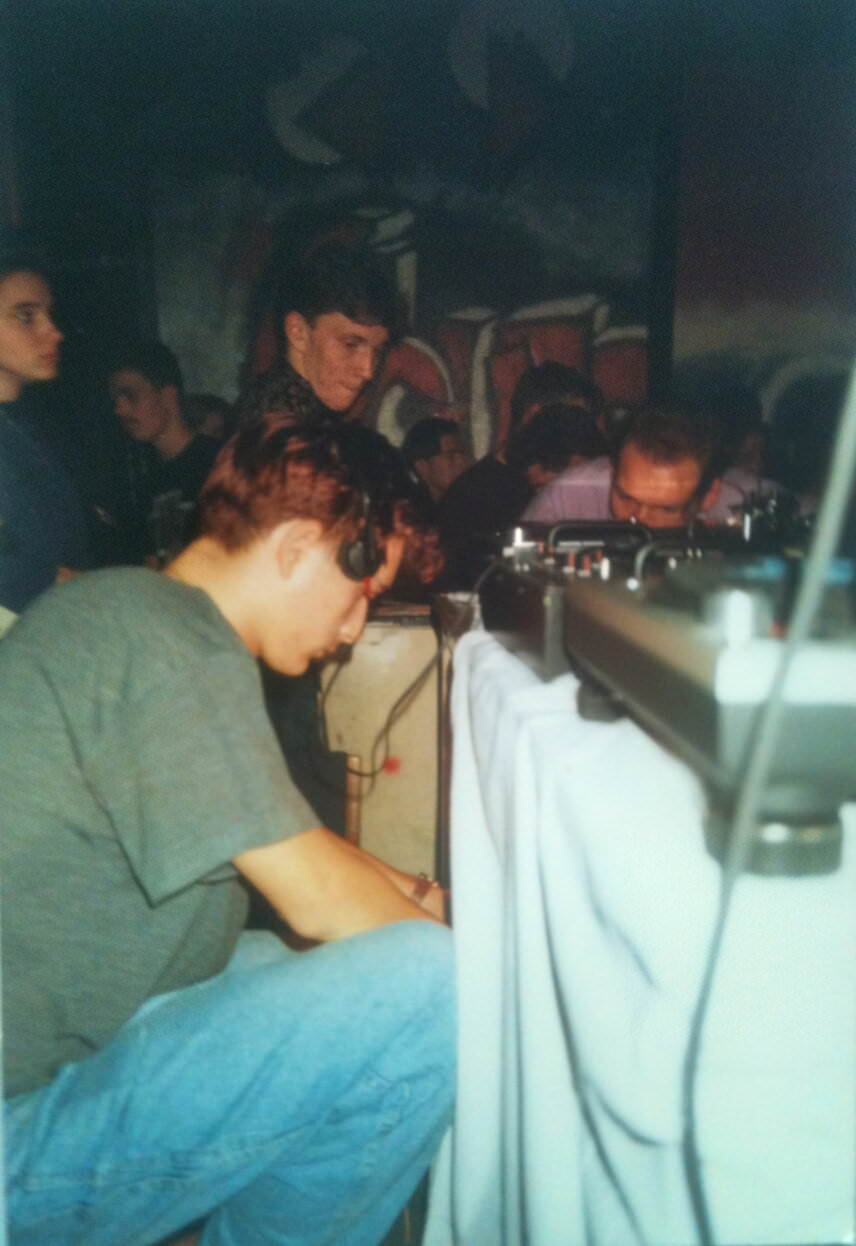

The young people from the East only got to hear about all this by secretly listening to the West’s radio, but music had just as much importance in their lives, if not more. “The music and the dance were a way of saying we have to renew ourselves, we want something different than marching together in uniform,” remembers Oliver Marquardt aka DJ Jauche (his brother is the infamous Berghain bouncer Sven Marquardt). Night after night, he sat in front of the radio to record tapes that he would then cut up and re-tape together during the day. “I wanted to become a DJ very quickly and also thought very early on that I had to leave the GDR to go to London and experience a warehouse rave there.”

DJ Jauche

DJ Jauche

DJ Jauche

When the Wall unexpectedly fell on November 9, 1989, the first thing he bought was a record player with pitch control, and the second trip to the West took him to record shops. In the meantime, Wolle XDP was drawn to the “UFO” on the very second day, where in the darkness he met many friends again who had already fled to the West before the fall of the Wall. “Because of the special audience in the “UFO”, it was one of the places where the East Germans were received quite openly. They weren’t West Berlin snobs, they were rather punky. There were pretty fucked-up people, some of them very poor.”

The music and the dance were a way of saying we have to renew ourselves, we want something different than marching together in uniform.

Even today, clear differences between East and West are noticeable, but these did not play a role in the emerging scene. Hegemann: “Reunification took place on the dance floor. The clubs were shelters that didn’t filter whether you were from the East or from anywhere in the world. Music was a binding element for the youth. What was also very binding was that it took place at night, in the dark.”

Arm in arm, the young people celebrated their newly won freedom – a political statement for DJ Jauche: “For both East and West, for everyone it was a completely new situation, and no one knew where it was going, but everyone had the feeling that now something really big was coming our way. The world is changing positively, everything is open to us. The people in the club were motivated in the same way. There was a special energy that comes with such a change.”

While the huge hype around the acid house was rescinding, it was techno that provided the soundtrack to this change. To be claimed by one side or the other, this music was too new. “Techno sounds to the untrained ear like noise when two things bang into each other and that’s exactly what happened at the time, two systems banged into each other,” says Thomas Andrezak aka DJ Tanith.

He, as well as other DJs, obtained their records from the record shop “Hard Wax” with a direct line to America, where techno had been developed by black artists in Detroit. Dimitri Hegemann: “The sound didn’t come from Berlin, Berlin provided the party. The prophets from Detroit were not honored in their own country. The balloon went up in Berlin.“

But the kids from the East in particular were clueless: “We didn’t care what the music was called or who was into it. All that mattered was that it was electronic and danceable,” Wolle XDP remembers. Soon he was organising the first raves in East Berlin with Tanith as headliner, whom he had discovered during one of the harder “UFO” nights entitled “Cyberspace”. “This music that Tanith played didn’t exist anywhere else. No singing, no piano, there was hardly any melody. There were only lasers, cannons, bombs, sirens, blatant beats, bass and robotic voices, white strobe and fog. When I heard the music, I knew I had arrived.”

Wolle’s goal was to enable a collective trance experience. He called it the “X-tasy Dance Project”, but it wasn’t about drugs, at least not for him. Dancing alone should be enough – but he didn’t leave it up to fate. There were no tables and chairs at the edge, lasers drew the eyes away from the dancers, the DJ stood on a pedestal barely 40 cm high: “On the dance floor, you have to design everything so that the people who want to dance and let themselves go feel superior to the people who don’t dance.”

Techno sounds to the untrained ear like noise when two things bang into each other and that's exactly what happened at the time, two systems banged into each other.

For the raves themselves, he chose the name “Tekknozid”. The two “K”s were intentional, because “techno” in Germany at that time described music like “Kraftwerk”, “Depeche Mode” or “Front242”, but had nothing to do with house. It was new that people from the West came to the East to party, and distributing flyers wasn’t easy, because there were no photocopying machines in the East, but the parties ended up being a great success.

Soon the most important club was also located in the East, in the cellar of an empty bank on the former death strip: The “Tresor””. According to founder Dimitri Hegemann, especially the supply of electricity and water was difficult at first. “The State Security had falsified all the plans of the building so that no one could escape underground to the West.” Like many others at the time, he started out illegally.

“Because the Wall fell, there were suddenly all these abandoned buildings where you could do what you wanted, along with the collapse of the system, where no one knew anymore what the law was, what was allowed, what wasn’t allowed,” DJ Tanith remembers. The police were too busy with other things to care and gave people the opportunity to experiment. “Nobody came and said you can’t do that, or you have to put down ten thousand dollars first. Those were the best conditions for a cultural new beginning, for the start of a whole movement into a new musical era,” says Hegemann.

According to him, the “Tresor” was a source of inspiration. Still gripped by the euphoria of the the fall of the Wall, people entered the club at night without great expectations and went home in the morning with thousands of new ideas. Everyone wanted to take part in this time of unlimited possibilities, and through many small start-ups, an economic force eventually emerged that has endured in Berlin to this day. The night time economy was born.

The window of anarchy, on the other hand, closed again in Berlin in 1993 at the latest, when not only authorities got wind of the scene, but also the industry. While DJs & Co had vehemently resisted marketing their music until then, the commercialisation soon culminated in the “Loveparade”, which grew from 150 to 1.5 million participants within just one decade and was broadcast live on television. Events like “Mayday” propagated a DJ cult by setting up large stages, which meant that part of the community spirit inherent in techno was lost, as everyone who set up techno in Berlin unanimously complains.

DJ Jauche finds it difficult to compare the spirit back then with the nightlife in Berlin today: “Nightlife in Berlin has predominantly become a business model. Very few clubs are about quality performance. As many big names as possible are brought in to fill the hut.” Before Covid-19, an estimated 10,000 tourists came to Berlin every weekend to party. Nevertheless, the vast majority of techno clubs in Berlin are still not run by big investors, but by people from the scene, as Wolle XDP says. “Outliers don’t stand a chance. They don’t work here.”

The sound didn't come from Berlin, Berlin provided the party. The prophets from Detroit were not honored in their own country. The balloon went up in Berlin.

No matter how you look at it, one thing is for sure: Techno has changed the image of the city forever. And if nightlife survives the pandemic, it is to be hoped that through a renewed change, people will rediscover what the music is really about, namely world peace.

If you want to learn more about the history of techno in Berlin, I recommend:

…reading:

- Felix Denk, Sven von Thülen: Der Klang der Familie. Berlin Techno and the fall of the Wall. English edition. Berlin: Suhrkamp 2014.

…watching:

- Maren Sextro, Holger Wick: We Call It Techno! A documentary about Germany’s early Techno scene and culture. Rough Trade Distribution 2008.

…listening to:

- DJ Jauche: Flashback 2021 – Oldschool Mix.