Tatsuya Takahashi is more than just your typical instrument designer. With interests in art and performance, his unique perspective has helped bring a number of synthesizers and drum machines to life for Korg and other manufacturers. He spoke to us ahead of his talk at the music conference, Most Wanted.

There are few gear designers that are known by name, but Tatsuya Takahashi a.k.a. Tats is the exception. In his 10 years at Korg headquarters in Tokyo, Japan, he worked on some of the most iconic synthesizers and drum machines of the 21st century: the Minilogue, Monologue, Monotrons, and early Volca line. He’s now heading up a new European branch for the veteran musical instrument company, Korg Germany.

We caught up with Tats in advance of the Most Wanted conference (November 3-5), where he’ll be giving a talk on some of his creations, entitled Instrument Design For The Powers Of Ten.

Attack Magazine: In the outline for your talk, Designing Gear For The Powers Of 10, you mention twice that certain designs (Triggers and Granular Convolver) were ultimately a good opportunity for study. Is study an important part of the process for you?

Tatsuya Takahashi: Yeah sure. Although I think insight and intuition are more important. Study is just one way to get them, amongst others. I guess the notes for my talk are describing how you can frame less commercial products as studies and make them sound like they have purpose. Haha. (They do!)

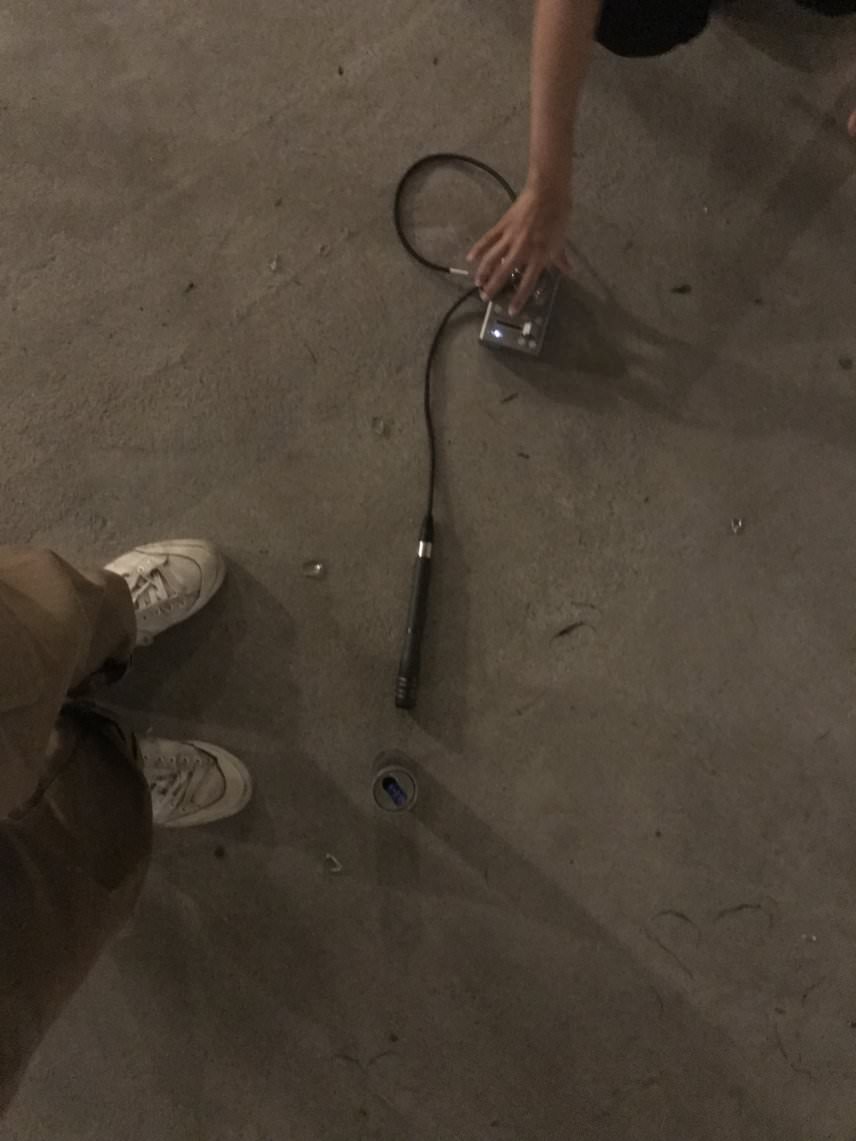

The Granular Convolver was basically a sampling box, barely labelled, that convolved real-time input with grains sliced from the samples. It was a musical device only made for the 60 participants of the 2018 RBMA in Berlin. Sixty is a very small number to produce and it meant that I could get to know every person who received it. I could be more experimental with this than with a mass-produced product. It was a bit of a mystery box and intentionally so because I knew I could spend time with the participants to figure it out together. I could hog their attention, which is a privilege you usually don’t have when launching a product. One of my best memories was climbing into the massive concrete attics of Funkhaus with Ramsha (awesome music by the way) and sampling glass and metal cladding.

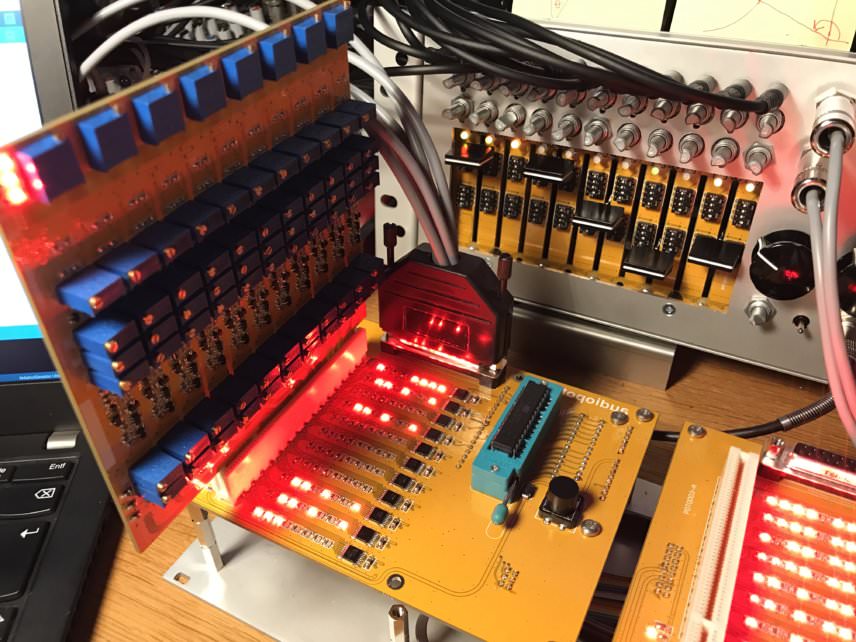

With Triggers, which was a personal project only for my own use, it is a whole bundle of studies.

- I’m putting audio rate triggers in the TR-808 sound generator circuits so it was a study of analogue convolution.

- I am using excel as a sequencer, so it was a study of numerical UI.

- The sequences are stored inside chips sitting on ZIF sockets which I swap out during performance, so it was a study of memory as physical objects.

- The sound circuits are actually hardwired PCBs that I would also swap around during performance so it was a study of timbre as physical objects.

- The TR-808 is the same age as me and has been so dominant in the scene that I work in, so it was a study of my relationship with the 808.

Actually the last one was the most important exercise: How to destroy and pay homage to the 808 in equal measure.

Attack Magazine: You were involved in the art project, A For 100 Cars. What was it about that project that attracted you?

Working with Ryoji Ikeda, who is just amazing and someone I’ve been a fan of for a long time. I remember I was so enthralled by his music that I changed my ringtone to a high pitched sine wave. I think it was really high like 14kHz or something. I loved it but it was probably really annoying for the people around me. Those that could hear it at least!

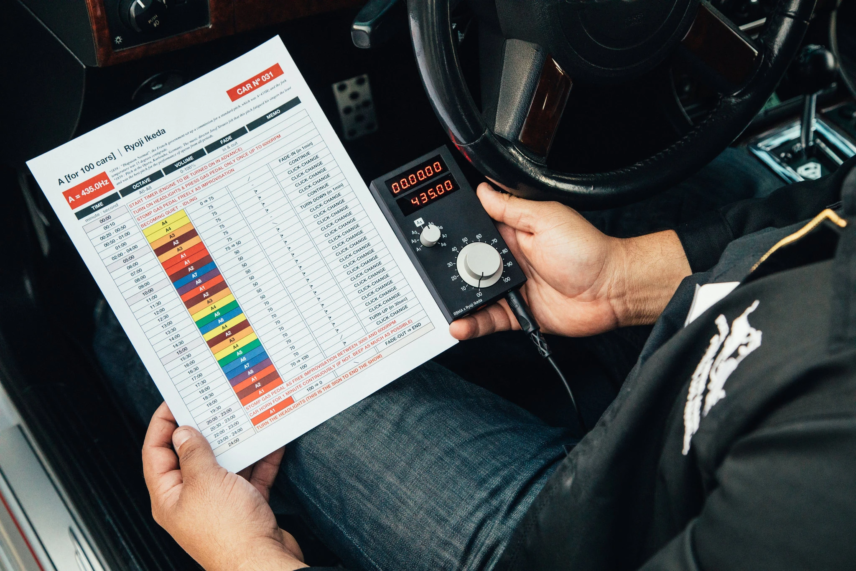

In a nutshell, A for 100 Cars was a drone piece composed by Ikeda, shown in downtown LA using the car stereos of 100 cars as the sound system. It was a massive, spatial drone piece using only sine waves, performed by the drivers following Ikeda’s 24-minute score.

I loved the fact that I was designing for car fanatics, not musicians. The actual owners of the cars were the performers of Ikeda’s piece, but most of them had no clue about Ikeda or sound installations. They just wanted to show off their tricked-out cars and insanely powerful sound systems. The brief I gave myself was: Design a device to turn 100 car lovers into performance artists.

I also loved the super high focus. Months of preparation just to make those 24 minutes beautiful.

Attack Magazine: And would you like to be involved in more pure art projects?

Yes!

Attack Magazine: What was your involvement in the E-RM Polygogo Eurorack oscillator?

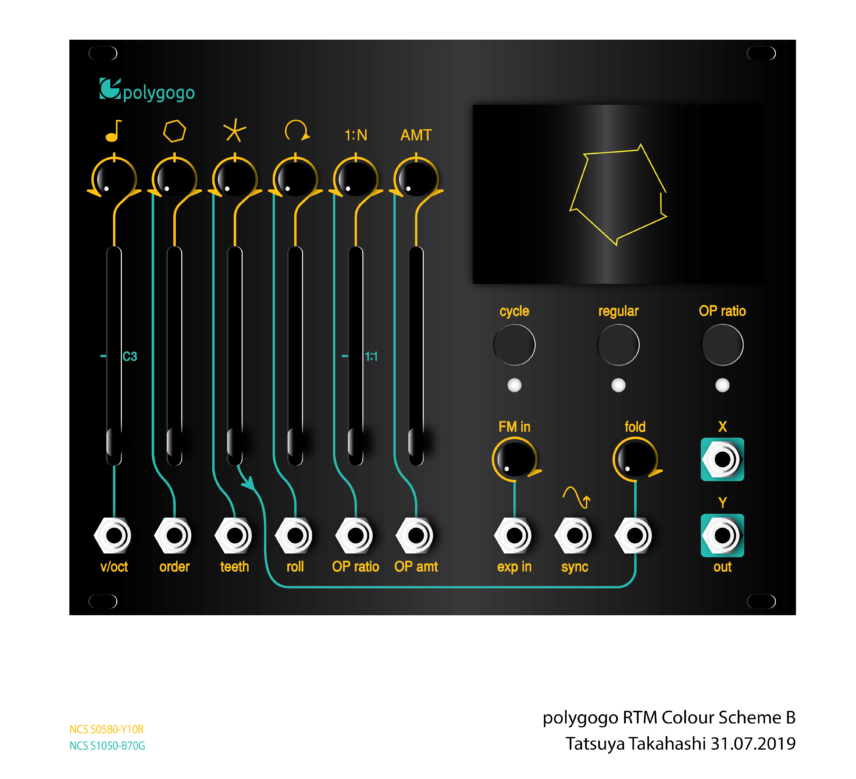

The Polygogo is a Eurorack module based on a visual, shape-based synthesis method invented by Maximilian Rest and Christoh Hornerlein. Max is somebody I’ve worked with very closely and he is now my business partner. We run Korg Germany together.

Anyway, for the Polygogo I worked on the physical UI and industrial design.

It just doesn’t make any business sense to enter a market only to destroy it, unless you are very short-sighted.

Tatsuya Takahashi

Attack Magazine: Would you like to do more Eurorack projects?

If I can contribute to the community, yes. I love the Eurorack ecosystem.

Korg is bigger than any of the major players in the Eurorack community, so we have to be careful about entering it. Not because we are nice. It just doesn’t make any business sense to enter a market only to destroy it, unless you are very short-sighted.

As Jacques Attali puts it, “Altruism is the most rational selfish behaviour”.

Attack Magazine: Are you a modular guy?

No. My day job involves connecting elements together to make complete instruments. When I play music I’m looking for a more curated and complete instrument.

Attack Magazine: Affordability has been a theme in your work, at least at Korg. Why was this important to you?

Synthesizers from the golden age are revered, coveted and command extremely high prices. Regardless of the justification of the prices, of which some are valid, it remains a fact that many of these great synths are out of reach for many musicians. Affordability in such a market is empowerment. Now that’s a very one-dimensional argument and it’s only one fragment of a more holistic view. Otherwise, you only end up putting out cheap ripoffs of old designs.

So here are some other fragments that I try to guide myself with:

- Stimulating the music scene. Do we want everyone using old synth designs to make music? I think it should be a nice mix.

- Sustaining innovation. Engineers and designers feed off creation, innovation and problem-solving. Kill that spirit and you’ve killed your company/team/self.

- Pedagogy. If kids can buy it, they’ll learn about it!

- Demographic. The market is still very skewed. How do we address this?

- Feeding the team. Bigger numbers mean that you can pay your staff and invest in future creations.

- Being respectful. We’re all standing on the shoulders of giants.

- Self-love. You poured your heart and soul into creating it. It’s nice when many people appreciate it.

You have to grapple with all of these at the same time, or you are not really doing much good to anyone. Including yourself.

Attack Magazine: In your talk, one of your points is designing instruments with a short learning curve. Is this to make them fun?

Yeah, not everyone wants to study!

Also personal preference. I have a terrible memory, so I hate coming back to a machine and having to learn it again.

Attack Magazine: With many of your instruments being both affordable and easy to learn, I feel like your products have helped lead to a democratization of hardware music making. Was this ever a stated goal of yours?

I can come up with a lot of grandeur goals in retrospect. But the reality is that I just tried to design products to be the best I can imagine them.

For me performing on the computer always felt a bit distant, so I tried really hard to make things interesting in hardware. When I started designing instruments professionally, flagship hardware instruments were workstations with loads of controls and huge banks of sounds. I found that boring and kinda fake because they were just computers in instrument skin.

Attack Magazine: You mentioned in an interview with NPR that you think there should be a synthesizer in every school. Why do schools need synthesizers?

My great teacher at Korg, Fumio Mieda, said to me once, “There is no distinction between rhythm and pitch. One is just faster than the other. Synthesizers are great because they don’t make this discrimination”. Mind blown. This kind of open thinking will make the world better and that’s why all schools should have synthesizers.

Attack Magazine: What is the function of Korg Germany within the larger company? Are you designing products for market or are you more R&D, or somewhere in between like the concept car section at a car company?

Korg Germany is a subsidiary of Korg, Inc. We are a small team based in Berlin taking on R&D and engineering. We are still in the first phase of the company, which is all about building the bone structure, training the muscles, test-firing synapses so we can work properly together. We are doing this by doing lots of prototyping and idea testing, all under a forced acceleration. It’s a really tough time right now because there is still a lot of friction, but once we have developed the agility to manoeuvre as a whole, we will move onto the real goal, which is mass-production design. So yeah, our purpose is to put products out that people can buy.

The biggest factor is that (Korg is) a family company and we don’t have to please money people. This is actually a superpower and one of the biggest reasons for me coming back to Korg.

Tatsuya TakahashiAttack Magazine: For me, Korg have always been risk-takers. Is that what originally brought you to them?

Kaoss Pad and microKORG brought me to Korg. Just like everybody else in the noughties! I simply thought they were really cool products and wanted to become part of the company.

I’m not sure about risk-taking, because there are lots of companies doing more risky things in this sphere. Since I know Korg from the inside, I can say that it really has a unique structure to allow interesting things to happen. The biggest factor is that it’s a family company and we don’t have to please money people. This is actually a superpower and one of the biggest reasons for me coming back to Korg.

Attack Magazine: Is your main focus still analogue subtractive synthesis?

Synthesis methods are just the means and were never the focus.

Attack Magazine: What is the next step for synthesis?

I’m trying to figure that out with my team! I honestly don’t know.

Attack Magazine: How important is collaboration with musicians when designing? I’m thinking of Richard James’ involvement in the Monologue, for example.

I think it can be really helpful to gain insight, but at the end of the day the designer needs to completely immerse themselves into and express the design. That gained insight needs to become the designer’s own. Otherwise, you’re designing from hearsay, which is fake and you’re dodging accountability of your design decisions.

As for Richard, he is a bit of an exception. I don’t really want to pass my judgement of him here, but because he understands so much more beyond sounds and synths, it was easy to integrate his opinions into the design.

Attack Magazine: Do you like having constraints? Would you like to design with no limits at all?

I love constraints and a state of no limits doesn’t exist.

Attack Magazine: What makes you fulfilled?

Pasta.

You currently have an ad blocker installed

Attack Magazine is funded by advertising revenue. To help support our original content, please consider whitelisting Attack in your ad blocker software.

x