Actress’s ‘Lost’ – 6/4

‘Lost’, from Actress’s 2010 album Splazsh, is an interesting example of a track which sounds quite simple at first but reveals hidden complexity.

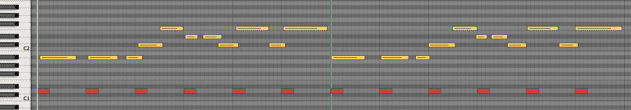

The time signature is best defined as 6/4. This is clearest at the beginning, where the bassline repeats every six beats:

However, things get more complex with the introduction of the loose triplets at 0:29, and then even more so at the end, where the introduction of the snare means the beat could be interpreted as a 4/4 pattern repeated every one and a half bars.

This is another great example of the ambiguity we discussed back in the ‘Dream Phone’ example. There’s a chance Darren Cunningham wrote ‘Lost’ with his project’s time signature set to 4/4, then included a 1.5-bar bassline loop, giving this unusual sense of timing to the track. It could be argued that the unconventional and unpredictable timing is a large part of what makes ‘Lost’ such a great track – it’s close enough to conventional 4/4 house tropes to sound familiar, but also different enough to sound original.

Venetian Snares’ ‘Szamar Madar’ – 7/4

Variations on 3/4 and 6/8 are relatively easy to follow (perhaps because they feature occasionally in familiar rock and pop tracks – try The Beatles’ ‘Norwegian Wood’ for one of the most well known examples), but things tend to get a little more difficult to follow as the numbers get bigger, particularly with odd numbers. Time signatures such as 7/8, 9/8, 11/8 and 13/8 might seem the kind of wilfully obscure choices you’d only expect to find in jazz or prog rock, but they can work effectively in some cases.

For something a little more unusual, let’s listen to ‘Szamar Madar’, taken from Venetian Snares’ 2005 album Rossz Csillag Alatt Született. Aaron Funk works extensively in alternative time signatures, with a particular fondness for 7/4 time. ‘Szamar Madar’ is based around a sample of Elgar’s Cello Concerto, which is in a 7/4 time signature (the original can be heard around 2:40 in this video).

The beat comes in at 2.30 in 7/4 time, with 7 crotchets in each repetition. The piece could perhaps be counted in 7/8, but notice how if we do that, the first beat of the second 7/8 isn’t emphasised by the sampled strings. 7/4 is the more logical choice.

Changing time signatures

We heard in Kenton Slash Demon’s ‘Ore’ how different time signatures can be used in certain section of a track to give a change of feel. Lastly, let’s consider the instrumental outro of ‘Hunger’, from Flying Lotus’s 2012 album Until The Quiet Comes, a piece of music in which the time signature changes even more frequently throughout a repeated section.

Starting from 2:20, the track’s time signature consists of four bars of 7/8, one bar of 6/8, one bar of 5/8, then back to 7/8, and repeat. On paper it’s staggeringly complex, but in practice it works surprisingly smoothly. A good reminder that just because you’re making music under the broad umbrella of dance and electronic genres, it doesn’t mean you can’t also get experimental with the most fundamental attributes of your music.

05.10 PM

nice read! I always loved how Daft Punk’s Revolution 909 switched from 2/4 and 4/4

09.48 PM

Adamski has been messing around with a lot of 3/4 lately with his neo-waltz concept https://soundcloud.com/officialadamski/neo-waltz-mixtape-2014

01.25 AM

Insanely informative and fun to read. Really great article.

01.35 AM

I really love the Bside of the first EQD single which switches between HP and LP filters every three beats on the synth but the main rhythm is a 4 to floor stomp, it’s a really cool effect.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DsDoLrzj8BM

10.41 AM

Music theory is the business. Love it. Thank you!!

03.50 PM

While this is a good article with a completely valid purpose, here’s a little known fact: 3/4 is still common to dance music if the waltz is your dance.

Just adding a little perspective to how we use words like ‘dance music’.

03.48 AM

I find it easier to think about odd meters as being just groups of 2s and 3s. “Take Five” can be counted as 3+2 in each measure – i.e. 2 beats of irregular length. Meters of 7 can be counted as 2+2+3 or 2+3+2 or 3+2+2.

In music theory terms, this is called “complex” meter, because the beats are not all the same duration. 4/4 and 3/4 are known as simple meter (the beats are divided in 2s) and 6/8 is compound (the beat is divided in threes).

01.51 PM

5/4, 7/8 ecc are “mixed meter” (don’t know if the term is right in english) .

Anyway it’s like what Olympia wrote, mixed (if we take in consideration 5/4) means 3/4 + 2/4 or 2/4 + 3/4.

While simple and complex meters can be divided by 2 or 3 (imperfect/perfect times as history teaches us) mixed meters are “simply” a sum of simple and complex meters.

04.09 PM

hi folks,

everyone interested in that topic should have a listen to burnt friedman, especially his ‘secret rhythms’ series which he did with can-drummer jaki liebezeit:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=57nCAOaCRto

a more popular example may be eskmos ‘gold and stone’ in 7/4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6iYQr5owmiY

for inspiration on odd meters, listen to bulgarian, turkish, greek, indian or yemenite folk music 🙂

08.09 PM

I would say the idea that 4/4 is the only ‘dance’ music is a very ‘sheltered Western DJ’ idea. Some interesting examples in this article, but from a very limited perspective- sure, if all you ever listen to is house music and its electronic derivatives, then 3/4, 6/8, 7/8 etc may come as revelations to you.

But open your eyes and ears and you’ll find that dance music comes in all forms and colors- all over West Africa, for example, people dance to 12/8 and 6/8 much more than 4/4. As Cito said above, in Bulgaria, Turkey, and Greece people dance to 7/8 more than 4/4. In India they may dance to 21/8. Don’t make the mistake of thinking of all these different musics as “world music”- they are “dance music” for people in cultures who get incredibly bored and don’t dance- trust me, I’ve seen it- if you put on the simple 4-on-the-floor 4/4 electronic music that we think of as dance music.

It would be much more interesting to create music inspired by these other kinds of dance music than to pick from the handful of non-4/4 examples in a very narrow EDM landscape.

09.25 PM

But where are the 2/4 time in dance? Hardstyle is really fast but because of the emphasis on a 2/4 lick instead of 4 on the floor I imagine it is easy to crossover, like this:

https://soundcloud.com/deadenz/save-the-day

05.22 PM

an old but classic tune from crystal distortion with different rythm structure here : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sbtlMOfviEc

01.05 PM

Finally a decent article on this. I’ve been searching for a week now and this is the best one thanks!

11.09 PM

A tubedrop to end this topic: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=28lUsDquJ70

Rigorously 11/16.

09.05 AM

Hi, Particularly Ezra

I’m trying to broaden my musical horizons into EDM and I should challenge you about how far you have to go to find non 4/4 dances – English folk dance music includes lots of 6/8 and 9/8 music – I do both social and sword dance (Northern England does sword dancing instead of Morris).