Photo: jacqueinabox.deviantart.com

A note on EDM and what it means for the rest of us

This time last year the spectre of EDM loomed ominously on the horizon. Mainstream America’s discovery of dance music had been rumbling along for a few years, but in 2012 we all seemed much more concerned than we do now. Was it about to swallow up the underground and spit it out, leaving a trail of destruction in its wake as we bowed to our new mouse-headed overlords? Of course not. With the benefit of another year’s perspective, EDM’s impact on the rest of dance music has been negligible. The underground – whatever you take that term to mean – remains intact, Ibiza wasn’t overrun with candy ravers this summer and Axwell hasn’t been booked to play Panorama Bar. If you were into dance music before EDM took off, chances are you’ve remained unharmed. No one’s forcing you to download the latest Guetta jams from Beatport.

Instead, we’ve seen a polarisation led by the financial might of SFX, the US media company with its sights squarely set on dominance of the lucrative North American EDM market. With SFX’s acquisitions including Beatport, ID&T, Miami Marketing Group and Made Event among others, it seems the company’s attentions are focused mainly on North America. Of course there are downsides to increased corporate interest in aspects of dance music culture, but they’re easily avoidable. Any DJ taking a gig at a Vegas or Miami bottle service superclub should know by now that the pay cheque comes with the risk of the promoter kicking you off the decks to suit the whims of the VIP section (and help drum up a bit of free publicity).

SFX’s activities in the hyper-corporate world of EDM don’t seem to have much significant impact on the rest of us. The further the EDM circus descends into the madness of pre-mixed DJ sets and elaborate stage shows, the more it defines itself as something distinct from club culture, house, techno, drum and bass and any other pre-existing genres you care to mention. It seems now that EDM is a genre in its own right, defined more easily by the culture itself – from VIP bottle service to kandi ravers and massive outdoor events – than by the various styles of trap, complextro and moombahton which make up its musical element.

This isn’t a value judgment, either: this isn’t an us-versus-them situation, it’s just different types of music doing different things. There’ll always be moments which cross over into our consciousness and raise an eyebrow, like Steve Aoki claiming to play deep house or – god forbid – describing his music as techno, but the impact is negligible. House fans getting upset about EDM makes about as much sense as jazz fans getting upset about rock. Live and let live. PLUR.

2013 in tech: more choice than ever

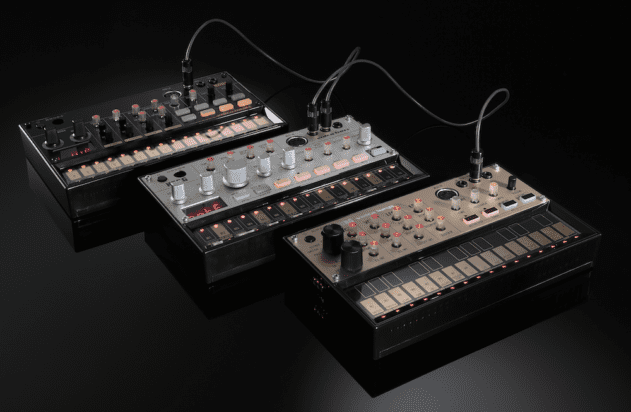

If 2012 was the year when the Arturia MiniBrute forced us to reconsider just how good a budget analogue synth could be, 2013 was the year affordable analogue became ubiquitous. The Korg Volca series and reissued MS-20 Mini, the Novation Bass Station 2 and the Arturia MicroBrute brought even more analogue options at ever-decreasing prices. Even the Moog Sub Phatty – admittedly a more expensive option than most of the others – brought Moog synths down to a more affordable price point.

2013 was the year affordable analogue became ubiquitous.

It all fit into a broader trend for music making. In house and techno circles this was the year when all-analogue hardware jams almost became an ideology. Of course, all this fetishisation of production methods is probably not entirely healthy. The idea of the all-analogue jam has become a selling point in itself, which is problematic for a number of reasons: primarily, it should be the end result which really matters, not the method used to produce it.

Nevertheless, the current interest in hardware-based workflows reflects the way musicians interact with their tools. Now that most producers have grown accustomed to the near limitless possibilities of software, it’s interesting how many of us are choosing to impose some limits. Hardware-based approaches often restrict us or force us down certain routes, but they also provide a clear focus and even define the sound itself. There are advantages to those limitations, and that’s a lesson we can all learn from.

In the constant ebb and flow of software and hardware trends, hardware was the clear victor in 2013. But it wasn’t the only area of music tech to develop rapidly this year. There was also a major trend for hybrid setups based around very focused, versatile controllers: think Ableton Push and the continuing popularity of NI’s recently expanded Maschine series. Throw in major upgrades to Logic and Ableton and too many brilliant new plugins to mention – 2013 was a very good year for dance producers.

03.45 AM

Cheers on this article, especially the section on EDM. You guys are a levelheaded bunch and I respect that. Keep up the good work!