Legato playing styles allow for smooth, seamless transitions between notes. Dave Clews explores how they can be used in your productions, as well as explaining the overlap with the glide and portamento functions found on synths and the tie or slide options on sequencers.

Taken from the Italian legare (“to tie up, tie together, to bind”), legato playing styles are all about making the transition from one musical note to another as smooth as possible, often using a particular type of playing – or ‘articulation’. If you think about a violin, cello or similar bowed instrument for instance, the term legato written on sheet music is taken as an instruction to play using the full length of the bow, employing a controlled wrist movement at each change of direction so that there’s a minimum gap or silence between notes. In other words, so that they flow smoothly into each other in a connected manner.

As an example of legato playing in a classical context, check out the orchestral strings in this passage from Johann Sebastian Bach’s Mass in B Minor:

Historically, legato as a style of playing started to gain popularity around the beginning of the 19th century as the romantic period came into full swing. One theory behind its growing popularity during this period was the emergence of new keyed woodwind instruments, such as the oboe and clarinet, that were much easier to play in a flowing, legato style as stopping and starting on them required a considerable effort! The long, sweeping string passages favoured by composers of the period also contributed to its increased use.

Legato is something of an umbrella term, taking on a number of slightly different connotations depending on both the context and the type of instrument being played. Legato playing on a guitar, for instance, involves using a sound with a long sustain and avoiding too much plucking of the strings with the right hand, instead using hammer-ons and pull-offs on the fretboard with the left hand to generate smooth runs of interconnected notes. Meanwhile, legato on a piano is achieved by a combined use of smooth fingering technique and the sustain pedal, which allows the notes to ring out while the hands are repositioned to play the next note or chord, at which point the foot can be lifted from the pedal so that the transition happens with minimal perceivable gap.

Legato is particularly effective on stringed instruments when the part allows for sliding between notes in a combination of legato and portamento (sliding from one pitch to another). Fretless bass has been out of fashion in recent years, but Pino Palladino’s masterful bass part on Paul Young’s 80s classic ‘Wherever I Lay My Hat (That’s My Home)’ is as excellent an example of legato playing as you’ll find.

What’s the opposite of legato?

By way of contrast, it’s worth compare legato playing styles to two techniques at the opposite end of the spectrum: staccato and pizzicato. Staccato playing can be achieved on most instruments and is characterised by short, sharp notes with plenty of space in between. Pizzicato is a technique specific to string instruments, in which the strings are plucked with the fingers rather than bowed, in order to give a sharper attack transient. Both techniques are used extensively across genres and imitated on synths, helping to give a more urgent sound than legato styles. Check out, for example, the pizzicato strings on Dizzee Rascal’s ‘Jezebel’, the day-glo metallic chimes on SOPHIE’s ‘HARD’ or the restless staccato synth programming by Juan Atkins on his proto-techno classic ‘No UFOs’:

Synth legato and glide

The development of commercial analogue synths in the 60s and early 70s led to the introduction of new legato options. Most early synths were monophonic (capable of playing only one note at a time) and manufacturers soon started to introduce ‘glide’ or ‘portamento’ settings, which allowed the synth to slide in pitch from one note to the next.

As an example of how these ideas were implemented in the first commercially available synths, let’s take a detailed look at one of the first big hits to feature a synth solo, Ike & Tina Turner’s 1973 single ‘Nutbush City Limits’:

The slidey solo in this rocking soul classic is a great early example of a legato synth solo in a pop record. It’s played on a Minimoog, an iconic monophonic synth of the era that had a glide setting, switched on and off using a rocker switch above the mod wheel and adjusted with a glide control on the front panel.

We’re going to take a quick look at how the synth would have to have been played to produce this effect, using Logic Pro X’s Retro Synth. Here are the notes that the solo plays, shown on Logic’s piano roll editor:

If we listen to this, it doesn’t sound right at all, even though the notes are correct:

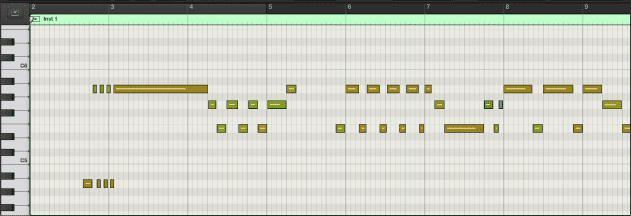

The reason is that legato mode is enabled on the synth, but in order for it to work properly, the notes in the solo need to overlap, so that the transition is perfectly smooth, and the synth has a base pitch to glide from. The original Minimoog could only play one note at a time, and with legato mode enabled, the lowest played note had priority. Here’s the same part again, with the notes overlapping to trigger the correct response from the glide parameter:

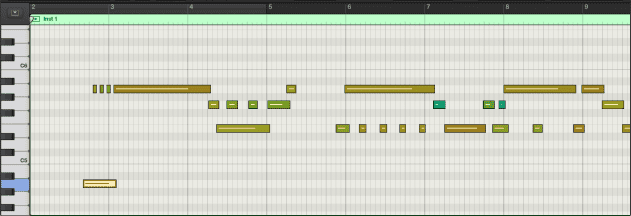

Note the trills played by tapping notes one note while holding down another.

And, as an illustration of how crucial the legato feature is as a component of the sound, here’s how it sounds with the notes still overlapping but the legato disabled on the synth:

The final result on the record is a combination of a particular setting on the synth (legato mode enabled, glide time around 80ms), combined with a programming technique designed to exploit the particular characteristics of that exact setting by overlapping specific notes.

On a monophonic synth (or a monophonic patch on a regular synth), the glide or portamento setting usually has a dedicated control, used to set either the amount of time it takes for the sound to reach the pitch of each newly played note or the rate at which the pitch changes. Some synths also offer a number of additional options, such as different legato modes and the ability to choose whether to retrigger amp and filter envelopes with each new note. The results can vary hugely depending on how the notes overlap and how far the distance is between successive notes.