Attack caught up with Italian house producer Riva Starr in his London studio to discuss his kleptomaniac musical style, the concept behind his new double album and why he decided to abandon the breaks scene.

With early releases on Claude VonStroke’s Dirtybird Records and Jesse Rose’s Front Room Recordings, Stefano Miele jumped straight in at the deep end when he began producing house tracks as Riva Starr. During Attack’s evening visit to his east London studio, Miele explained how he’d already earned a global reputation producing breakbeat as Madox, but chose to start again from scratch, building his new identity via music blogs and social media.

Despite international success as an artist, a producer and a remixer, Miele refers to himself primarily as a DJ. This focus on the club experience and the importance of the dancefloor is reflected in his music, which is characterised by an unashamed element of fun. If you like music to be po-faced, ultra-serious and lacking any sense of humour, Riva Starr may not be for you, but the success of tracks like the Balkan-influenced ‘I Was Drunk’ suggests that the formula works.

Emphasising the importance of originality and attention to detail throughout, Stef let us in on the secrets of his music, from his roots in southern Italy through to his recent obsession with prog rock and the importance of breaking the rules.

Attack: Let’s start by talking about how you first got into music.

Riva Starr: The south of Italy has a very strong musical tradition. Naples, where I come from, has a lot of influence from Africa, Spain, Greece and the Balkans. Northern Italy has a type of music we call combat folk – which is almost Celtic in a way – but there’s not a proper root or culture to it because of the history of different people who lived in that area over the centuries. Southern Italy has a very rich musical culture. I was born there and grew up there, so in my music you can hear all those different influences.

At what point did dance music come into your life?

When I was at high school I listened to mix shows on the weekend from one of the big clubs in Naples, then me and some friends decided to start doing parties. We used to do 18 year-old birthday parties: a big cake at midnight, sing ‘Happy Birthday’ then play Gipsy Kings megamixes and all that bullshit! To get started I made enough money to buy turntables, a mixer and a few records but for a while I was playing five hour sets with about twenty or thirty records, playing the A-side, the B-side, the instrumental, the acapella, trying to make brand new records from them…

And from there you got into producing your own tracks?

Around the late 80s I got into production. We were really into all the latest technology so we were using an Atari as a sequencer, an Akai S950 sampler and we started making edits with the first digital multi-tracks. I started off doing megamixes and remixes of all the tracks on the radio, then slowly got into proper production.

After a while I realised I was basically a DJ rather than a musician, because I can hardly play any chords, so I got into full-time club production making drum and bass as Stefano Miele. I produced a few drum and bass tracks but I wasn’t really into it.

When the nu skool breaks scene exploded with all that stuff from Plump DJs, Meat Katie, Rennie Pilgrem, Tayo and those guys I got inspired to start playing and producing breakbeat. I was probably one of the first in Italy to push breakbeat and I was flying to London every month to buy records at Vinyl Addiction and in Soho. Then I started the Madox project with Mantra Breaks and we were touring worldwide, from Japan to London to America.

After four or five years I got bored because the scene was slowly dying. There were no new ideas and no new tracks. We were just playing our own stuff and it was like, ‘You know what? This isn’t fun any more.’ New crossover music was coming from house from guys like VonStroke and Jesse Rose, then all the early fidget house when it wasn’t that cheesy and it was still very cool. It really convinced me to move to four on the floor beats, so I left Madox behind in 2006 and moved to London.

Was it a deliberate effort to start all over again with the new project?

I started from scratch. I’ll never forget, I was playing as Madox at Womb in Tokyo one week – one of the biggest and best clubs in the world – and then two weeks later I was playing in a pub in London for 50 quid. It was hard work. In the first two years as Riva Starr I did over 70 remixes, but I started in a good way because the first release was on Dirtybird and then the second was on Front Room.

It took me a while to rebuild my style and move from the breakbeat sound with big basslines to the house music thing, but it’s not easy. Most of the breakbeat producers who moved to house were all doing the same kind of big room electro/fidget thing, but I definitely wasn’t into that so I tried to make my own style.

You can hear in the first few Riva Starr releases that you were still looking for your sound.

Yeah. The turning point was ‘Maria’, the first track I released on Kindisch, the Get Physical sub-label. That was the track that really got me into my sound. Sometimes it’s not easy to do that. If you’re the kind of person who’s played pretty much the same thing for ten years, you might worry about using a sound that’s too different to the rules of the genre. For me, if a sound is good there’s room for it in the track, even if it doesn’t fit the usual rules.

I think the best records have always been the crossover ones. Sometimes – most of the time – artists are afraid of breaking the rules so they go in a safe direction. If I put out a record with a reggae sample or something it doesn’t mean that I want to go mainstream or commercial or whatever, it’s just that I’m trying to put some different culture and sensibility in the tracks and make something different.

There’s no point in producing stuff that a thousand other DJs are producing. Over the last few years people have started recognising my sound and that’s good for me. Whether it’s in a good or a bad way, I don’t care.

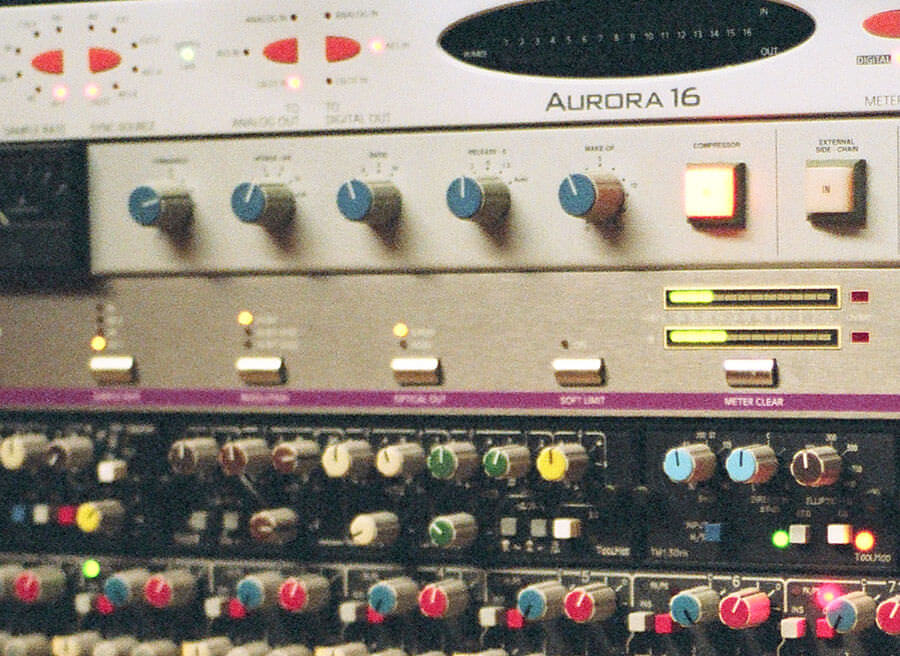

The riva rack

Roland SH-101

It still sounds so good. For basically the first two years of Riva Starr productions, all the synth sounds and the bass came from this.

SSL G series mix buss compressor

I use this for drums. I don’t like to put compression on the whole mix. I’d rather work properly on compressing the drums, bass and kick, then go into a good limiter and leave all the extra work to the mastering.

Empirical Labs Distressor

I use my Distressor all the time. I’m going to buy a second one so I can use one for the kick drum and one for the bass.

12.03 PM

Good questions. Riva is the man!

12.04 PM

Some serious sick kit there, damn,